Broken

This is Western Coffee—notes on building the creative body. Last time: Custodian. The whole series is here. Please share this email; you can sign up free below.

Ten years ago today, I went for a bike ride in Prospect Park on a brand-new Cervélo. Then I came home and got ready for work. I was trying to cycle into the office more often, so I packed up my food for the day and a change of shoes and pedaled over the Williamsburg Bridge and up through Allen Street to First Avenue, which I planned to take all the way up to Midtown.

In the middle of 14th Street, hurrying through a yellow light, I failed to notice some rough pavement until it had shaken my hands loose from the still unfamiliar handlebars and I’d crashed down on a curb by the north crosswalk. I knew I’d hurt myself very badly as soon as I tried to stand up; one leg wouldn’t bear any weight at all. Beth Israel Medical Center loomed two blocks away, so I turned my bike into a walker.

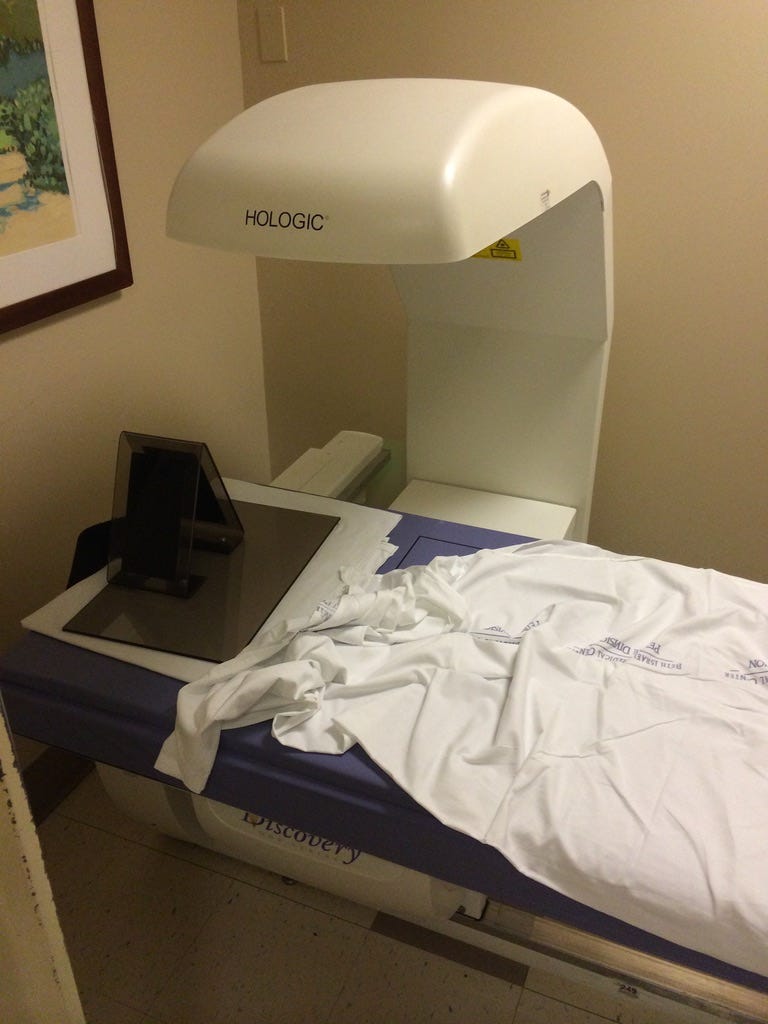

Because I didn’t get there in an ambulance, the emergency department stalled me with paperwork. When I began to scream like Westley in the Pit of Despair, they took me in for evaluation. But the doctor couldn’t see a fracture on the X-ray. I had my own expertise in bone fractures (of two femurs, my collarbone, my pubic bone, and a rib) and assured him that something was broken, but he refused further imaging and referred me for a follow-up with an orthopedist. They sent me away with a set of crutches.

As it turned out, my pelvis had broken in three places. The results of the MRI came by phone call to Utah, where I’d traveled for my grandfather’s funeral. I could only laugh when the orthopedist told me that it was critical, because of the site of one of the fractures, to keep using crutches. I hadn’t brought them on the trip.

What followed outdoes some other pretty tough years for the worst of my life. A femur break like each of the two I’d had in my 20s is no joke, but in those cases the remedy had been surgical, and the recovery straightforward. With physical therapy, I was back to normal function within a few weeks. But this time around I would just have to wait for the bone to heal, and as I did, the pain dug in for the long haul.

The orthopedist sent me to a rheumatologist to figure out why my bones kept breaking, and she quickly figured that out (idiopathic hypercalciuria) and treated it (a diuretic). But the pain persisted. I saw many other orthopedists—different specialists for each of the places the pain migrated, from my spine and hip to my ankle. The rheumatologist ordered literally 99 tests—“zinc, whole blood”; “lupus, PTT”; “TTGAB REFX ENDOM AB”—and sent me to a urologist to check one thing and a hematologist to screen for another. A genetic specialist ran a test for a rare autoimmune disorder. A cardiologist did an echo to see if I had Marfan syndrome. I can still summon my fury when the second endocrinologist I saw told me, a little sternly, that my bone density (which was objectively near osteoporosis) was merely on the “low end of normal” and not the explanation for my fractures or related to my pain. (Some doctors are just straight-up idiots.) A physiatrist injected me in the lower back and I felt tingling in my toes for two days, but no relief. Less than a year before the crash, my left retina had partly detached, and for a while it felt as if something was wrong with all of me at once—but two dozen New York City doctors couldn’t say what. I started binge eating so relentlessly that I had to leave my therapist, who told me that it was the essence of humility to understand what would be truly necessary to accomplish something, and he realized he couldn’t help me with this.

I don’t know what would have happened if the new therapist I stumbled across hadn’t mentioned John Sarno, an unorthodox physician at NYU. Sarno hypothesized that most back pain—and by extension much other chronic pain, and a litany of other diagnostically elusive ailments—had an emotional rather than a physical origin. He wasn’t saying that patients made their pain up; rather he believed that the brain sometimes diverted even ordinary stress (and oft-censored emotions like sadness and rage) into a physical rather than a conscious emotional manifestation. Forty years later, in an age of entire podcasts about the nervous system, this reasoning has moved from speculative to “no shit”—but Sarno’s methods weren’t scientific, and pain management as a whole has resisted their underlying truth.

Sarno saw a lot of, shall we say, equanimity-forward people who acted as shock absorbers for people and situations around them; but that shock had to land somewhere, and where it landed it produced symptoms. The cure was not a pill or more physical therapy or even acupuncture: The cure (which, heretically, was free and self-administered) was to accept that this was happening and then to search out perhaps unacknowledged stressors in your life—from childhood, from relationships and responsibilities, from desires to do well and do good—as if you were an impartial detective. You had to figure out what emotional pain your brain was hiding from you, and ask it not to hide it anymore.

It took a few more years for me to embrace Sarno’s arguments—to really believe that my symptoms had something other than a one-to-one relationship with the physical state of my body. When I did, after a seminar by Sarno’s protege, the last of my pain vanished within hours. A couple years later, I took up the question of running, which had seemed like a fantasy since my first femur break in 2007. Less than six months after that, I finished the Malibu Triathlon.

I still lose a week or two of running now and then to an achey foot or a low-back spasm; the sooner I remember to look myself in the mirror and invite a conversation, the sooner it goes away. This process used to tend toward scolding: “I need you to stop putting the anger in my knee. Just let me be angry!” The more I’ve done it, though, the more it feels like I’m checking in with someone I love: “How are you? What’s really going on here?”

If you’ve read Western Coffee for a while, some of this is a rerun. But I wanted to go back into it on this anniversary of my accident because of the way it rewrote my life to learn that I didn’t need anything I didn’t already have to heal things that had felt irretrievably broken—a lesson perhaps as profound for many creators as it is for the athlete. As I sat down to work on this post, I got an email from the Ironman organizers about registration filling up for the 140-mile mountain ordeal in Lake Placid next year. By the time I started writing, I was registered.

If you enjoy Western Coffee, please make a donation on my fundraising page for the nonprofit Achilles International, which is how I’m gaining entry to the New York City Marathon this year—my first.