Attention

This is Western Coffee—notes on building the creative body. Last time: Silence. The whole series is here. Please share this email; you can sign up free below.

In my last year at college, I found myself paralyzed by the obligation of my senior thesis. I don’t remember what I intended to write about, only that it wasn’t happening, and this state of affairs persisted through two rather diverting semesters. I cemented friendships with people I’m still close to, and listened to the (pre-Spotify) infinitude of music afforded by campus-network piracy, and read a physical copy of The New York Times at the sunny cafe tables near the mailroom. I threw a Valentine’s Day party with a cocktail menu. I typed nearly verbatim notes in a seminar on Heidegger. I Netflix-and-chilled.

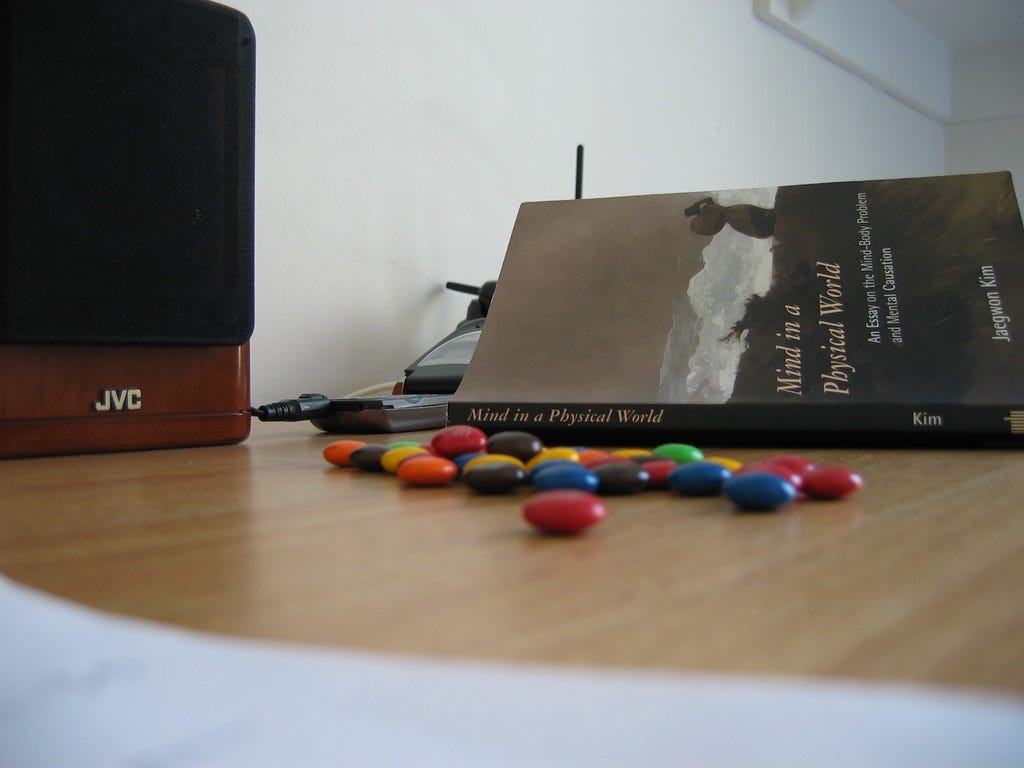

The thesis, which ended up being on the hard problem of consciousness, took five additional years to write. In the meantime, I moved to L.A. and worked at The Huffington Post and then The Los Angeles Times, where I helped run the home page—using some very bootleg code-writing skills to build custom designs for the second election of Governor Schwarzenegger (that spelling still spills effortlessly from my fingers) and the first of President Obama. I joined the standards committee and wrote a web style guide and trained for the AIDS/LifeCycle bike ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

The big contrast between these two periods of life—during college and after it—is how much easier it was in the second to get any work done.

I used to think this was because the stakes were higher: The real world doesn’t come with a dining hall. But I’ve realized that what the working life asked of my attention was totally different from what my senior year of college had; and that what it gave back was an almost continuous sense of completion and advancement.

Almost as soon as I began working I devised, very much by necessity, a running to-do list, a descendant of which remains the organizing principle of my life. Because everything was on it, it became a dance of the things I loved doing and the ones I loathed and the great middle between them.

And suddenly the task of working was not: “Produce a voluminous piece of writing that demonstrates your acquired worthiness to receive a baccalaureate.” It was: “Edit this 400-word blog post,” or “fix the HTML in this buggy module,” or “forward this message from the boss,” or “update this spreadsheet,” or ”answer your texts.” The stakes were in one sense lower, even as the work became more consequential.

Furthermore, each day consisted of many such smaller things, and it was possible—even necessary—to switch constantly among them. When I started at The New York Times, in 2011, things sped up: There were more stories moving on and off a more visible and dynamic home page, and elsewhere on the to-do list I was acquainting myself with a new city. I worked an eight-hour shift and left my desk only to use the bathroom. Even when I started collaborating with other divisions of the company, a few years later, and then leading a team, the days were modular: a 30-minute check-in here, a design review there.

Two years out of an office job, this is still essentially my approach to time. One thing that might be even more paralyzing than writing a senior thesis is writing a novel. But just writing a few dozen or hundred scenes—and interspersing this work with contrasting and complementary categories of endeavor, like triathlon training—that’s just kinda fun.

Thus, I’m not going to take this reflection toward a critique of our fractured attention economy, though I’m working on a piece for publication elsewhere right now that will tread some of that space. My point here is kind of the opposite: Some people’s brains work better—work well—in the state of fracture. It’s something our culture loves to pathologize, so much so that we are now short on the corresponding medication. With respect for everyone’s experience, I’m skeptical. There are many destructive forces in modern life working against our ability to focus; but I think nature gave some of us rotational attention as an asset. What if your way of paying attention is the right one, and it’s the work that’s in need of adapting?

Kindly send me your thoughts, questions, and provocations: dmichaelowen@gmail.com. And say hi on Instagram, or let’s Peloton together: @leggy_blond.